Every morning, millions of people reach for their coffee believing they understand a simple transaction: farmers grow beans, someone roasts them, stores sell them. This mental model couldn’t be more wrong. Your coffee has traveled through 8-12 different hands across 5,000+ miles and multiple continents before reaching your cup—a journey so complex it would puzzle medieval spice merchants, yet deliberately hidden beneath pastoral marketing images of smiling farmers.

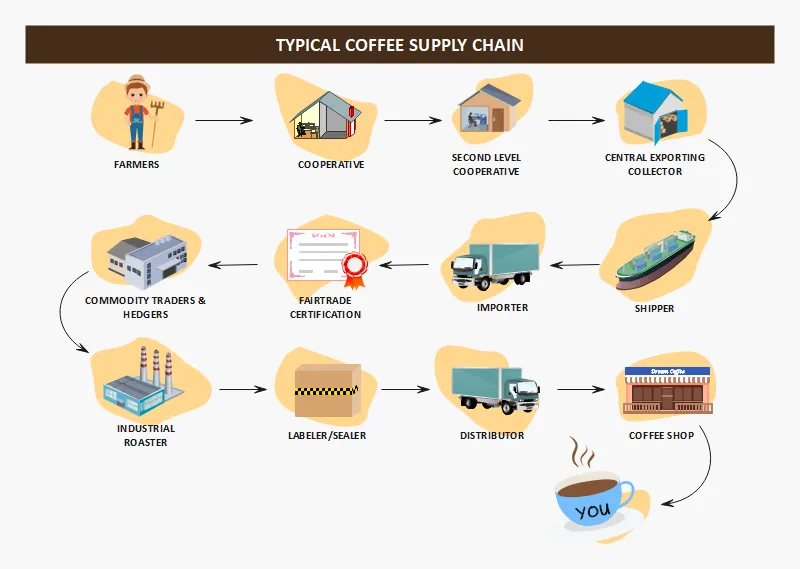

The coffee industry has constructed one of the world’s most elaborate supply chains, involving more intermediaries than almost any other consumer product. By the time that Ethiopian bean reaches your local café, it has passed through collectors, processors, exporters, commodity brokers, importers, roasters, distributors, and retailers—each adding their markup while farmers who bear all the production risks receive just 10-13% of what you pay.

This matters because understanding coffee’s hidden journey reveals how modern global trade actually works. The same forces that once made simple spices worth their weight in gold—geographic advantages, processing control, and information asymmetries—operate in your morning routine, just hidden beneath layers of complexity that would astound our ancestors. Coffee represents the perfect case study for how distance and intermediaries create value extraction systems that benefit everyone except the people who actually grow what we consume.

The great deception of coffee simplicity

Here’s what the coffee industry doesn’t want you to know: that bag of coffee in your pantry has traveled further and through more hands than most people travel in their entire lives, yet this epic journey is deliberately obscured from consumers through marketing that suggests direct farmer-to-consumer relationships.

Most people imagine coffee production as straightforward—farmers grow beans, someone buys them, they get roasted and sold. This mental model misses the staggering reality. Coffee’s supply chain involves more intermediaries than oil, more documentation than international banking, and more quality checkpoints than pharmaceutical manufacturing. Yet unlike these other complex industries, coffee marketing actively promotes the illusion of simplicity through pastoral imagery and “farm-direct” messaging that hides the true complexity.

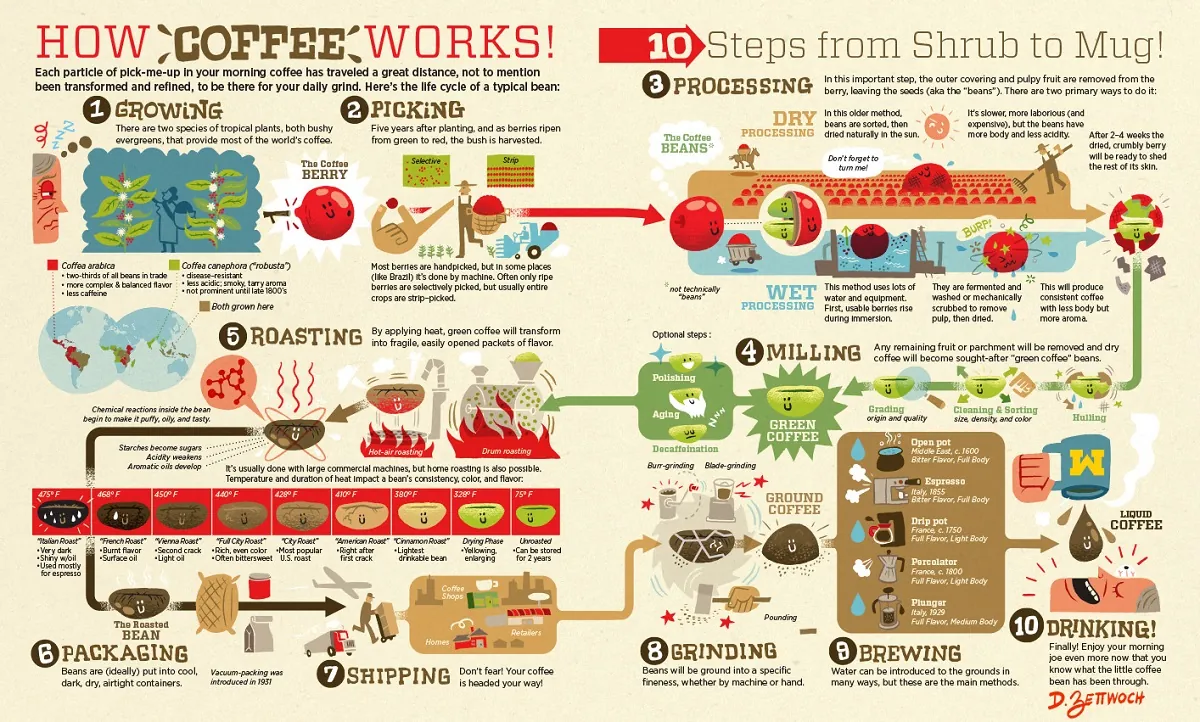

Consider what actually happens when coffee leaves a farm in Ethiopia’s highlands. The journey begins when individual farmers sell small harvests to local collectors who aggregate production from dozens of smallholders. These collectors transport coffee to processing stations where it undergoes wet or dry processing—each method dramatically affecting final quality and value. Next comes grading at the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange, followed by sale to licensed exporters who handle quality certification, documentation, and international shipping.

The beans then travel 4,000+ miles to importing ports like Hamburg, where specialized coffee importers handle customs clearance, warehouse storage, and quality control testing. From there, coffee brokers may purchase and resell to roasters, who finally process the green beans into the familiar brown coffee. But the journey isn’t over—distributors transport roasted coffee to retailers, who finally sell to consumers.

Each step involves different companies, currencies, quality standards, and profit margins. A typical coffee shipment requires 15-20 different documents including bills of lading, phytosanitary certificates, certificates of origin, quality reports, insurance documents, and customs declarations. This bureaucratic complexity exists nowhere in consumer marketing, creating a massive information asymmetry between industry reality and public perception.

The Marketed source of your coffee [left]; vs Hidden Supply Chain of your Coffee Cup [right]

Following the bean through its secret odyssey

The economic archaeology of coffee’s journey reveals why this complexity persists and benefits almost everyone except farmers. Each intermediary step serves specific functions while capturing value, creating a system where geographic distance becomes profitable complexity rather than mere logistics.

Local collectors serve the essential function of aggregating small harvests from individual farmers who typically grow 1-5 acres each. Ethiopian smallholders cannot economically transport 50-100 kg of coffee beans to processing facilities or export markets, making collectors necessary intermediaries. However, collectors also exploit information asymmetries about quality and pricing, often paying farmers uniform prices regardless of bean quality that will later command premium prices.

Processing stations add genuine value by converting raw “cherry” fruit into stable, tradeable green coffee beans through either wet processing (fermentation and washing) or dry processing (sun-drying whole cherries). This processing determines fundamental quality characteristics and storage stability. However, processing facilities often capture 20-30% of coffee value despite farmers bearing all production risks, including weather, pests, and market volatility.

The Ethiopian Commodity Exchange provides price discovery and quality standardization, theoretically benefiting farmers through transparent pricing. In practice, quality premiums discovered at the exchange rarely flow back to farmers, who have already sold their coffee to collectors at predetermined prices weeks or months earlier.

Export operations handle the complex documentation, quality control, and logistics required for international shipping. Coffee exports require phytosanitary certificates proving absence of pests, quality certificates verifying grade standards, certificates of origin for trade preferences, and specialized shipping containers that maintain temperature and humidity controls during 6-8 week ocean voyages. These services add genuine value but exporters typically capture 10-15% margins while farmers receive payment only after successful export completion.

Import and distribution operations in consuming countries handle customs clearance, port logistics, warehouse storage, and domestic distribution. Major importing ports like Hamburg maintain specialized coffee storage facilities with capacity for 60,000+ tons, climate control systems, and sampling facilities for quality verification. Coffee can remain in warehouse storage for 6+ months while importers wait for optimal market conditions, capturing seasonal price variations that farmers cannot access.

Roasting operations represent the highest value-addition step, converting stable green coffee into the aromatic brown beans consumers recognize. Roasting determines final flavor profiles, quality grades, and premium positioning. Roasters typically capture 30-40% of retail coffee value despite purchasing pre-processed, quality-certified raw materials with minimal remaining risks.

The mathematics reveal the journey’s value extraction: farmers receive $1.20-1.80 per pound for coffee that retails for $8-12, yet bear 100% of production risks including weather, pests, theft, and market volatility. Meanwhile, each intermediary captures predictable margins while providing specialized services that create genuine efficiencies alongside systematic value extraction.

Why the complexity evolved and persists

Coffee’s elaborate journey didn’t emerge by accident—it represents the logical evolution of geographic and economic realities that make complexity profitable for everyone except producers. Understanding why this system developed reveals fundamental patterns about how global trade creates and maintains value extraction relationships.

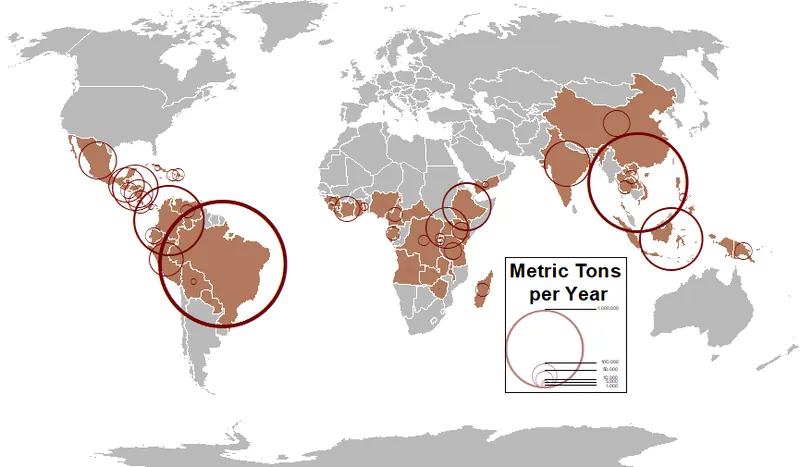

Geography Constraints: From the Coffee Belt [left]; and the Coffee Consumption map [right] Bamse, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons Cbahrs, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Geographic realities drive the initial complexity. Coffee grows only in specific climate zones between 25°N and 30°S latitude, primarily in mountainous regions of developing countries far from major consumption centers. Coffee-growing regions typically lack the infrastructure, capital, and expertise required for processing, quality control, international shipping, and market development. This geographic mismatch between production and consumption creates natural opportunities for intermediary services.

Scale mismatches perpetuate intermediary dependence. Most coffee farmers cultivate 1-5 acres producing 500-2,000 pounds annually—far below economical shipping quantities of 37,500+ pounds per container. Aggregation services become essential but create dependency relationships where farmers must sell to collectors who control access to larger markets. Small farmers cannot afford the $15,000-25,000 costs of direct export licensing, quality certification, and international shipping.

Technical expertise requirements favor specialized intermediaries. Coffee processing involves complex chemistry affecting acidity, sweetness, body, and aroma that determines final value. Optimal fermentation timing, drying curves, moisture content, and storage conditions require expertise that smallholder farmers often lack. Similarly, international trade involves documentation, quality standards, shipping logistics, and financial instruments that favor established players with specialized knowledge.

Information asymmetries maintain profitable complexity. Farmers selling to collectors rarely know current international prices, quality premiums, or market conditions that determine actual coffee value. Price information typically travels down the supply chain with significant delays and filtering, enabling each intermediary to capture margins based on superior market knowledge. Even when price information exists, farmers lack alternative buyers or storage capacity to negotiate effectively.

Financial structures perpetuate dependency. Coffee farmers face immediate cash needs for living expenses, farm inputs, and family emergencies, while coffee sales provide income only during harvest seasons. Collectors and processors provide essential credit and advance payments that create dependency relationships extending beyond simple commodity transactions. Farmers who receive advance payments become locked into selling to specific buyers regardless of market conditions.

The persistence of this complex system reflects its effectiveness at capturing value while providing genuine services that create overall economic efficiency. Each intermediary step adds real value through aggregation, processing, quality control, logistics, financing, and risk management—making the system economically rational even as it concentrates profits away from producers.

Modern relevance: What coffee’s journey reveals about global trade

Coffee’s hidden journey matters far beyond your morning routine because it illuminates fundamental patterns about how global commerce operates in interconnected economies. As supply chain disruptions, climate change, and technological innovation reshape international trade, coffee serves as the perfect laboratory for understanding how complex systems adapt while maintaining underlying power relationships.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed coffee’s supply chain vulnerabilities in ways that mirror broader global trade dependencies. When container shipping costs increased 300-400% and port delays extended to 6+ weeks, coffee prices became disconnected from production costs while farmers faced input cost inflation without corresponding income increases. Coffee’s complex intermediary network amplified rather than absorbed these disruptions, demonstrating how geographic distance and complexity create systemic fragilities.

Climate change threatens coffee’s geographic foundations in ways that parallel other location-dependent industries. Rising temperatures, changing rainfall patterns, and extreme weather events affect 50% of current coffee-growing regions, forcing production into higher altitudes and different latitudes. Coffee’s complex supply chain must adapt to shifting production zones while maintaining quality standards and economic relationships, offering insights into how other industries will navigate climate-driven geographic changes.

Digital technology promises supply chain transparency that could revolutionize coffee’s traditional opacity. Blockchain platforms enable QR code tracking from specific farms to retail purchase, while satellite monitoring can verify production practices and environmental compliance. However, technology adoption often excludes smallholder farmers who lack digital infrastructure, potentially creating new forms of market exclusion alongside traditional geographic barriers.

Direct trade movements attempt to bypass traditional intermediaries by connecting roasters directly with farmers through digital platforms and relationship-based purchasing. These initiatives demonstrate both the potential for supply chain simplification and the persistent challenges of scale, logistics, quality control, and financing that historically justified intermediary services. Direct trade’s mixed success illuminates which intermediary functions add genuine value versus pure extraction.

Consumer awareness of supply chain complexity grows alongside demand for transparency and sustainability. Modern coffee consumers increasingly seek information about origin, farming practices, and farmer compensation that challenges traditional industry opacity. This consumer pressure creates market opportunities for brands that can credibly demonstrate simplified supply chains or equitable value distribution.

Understanding coffee’s journey provides crucial insights for analyzing other global industries and recognizing persistent patterns underlying apparently modern trade relationships. The same dynamics operating in coffee—geographic concentration, scale mismatches, technical expertise requirements, information asymmetries, and financial dependencies—shape everything from lithium mining to semiconductor manufacturing.

Coffee demonstrates that technological sophistication often obscures rather than eliminates fundamental geographic and economic realities that create opportunities for value extraction. Recognizing these patterns helps evaluate claims about supply chain innovation, sustainability initiatives, and fair trade programs across various industries.

Your morning coffee connects you to a 5,000-mile journey involving dozens of intermediaries, multiple currencies, and complex quality standards that transform a simple agricultural product into a global commodity. Understanding this hidden complexity reveals not just how coffee reaches your cup, but how geographic distance, specialized knowledge, and information asymmetries continue to shape value distribution in our interconnected world.

The next time you take that first sip, remember: you’re consuming the end product of one of humanity’s most elaborate supply chains—a journey that reveals fundamental truths about how global trade actually works when complexity becomes profitable for everyone except the people who grow what we consume.

Check out this overall supply chain representation by Visual Capitalist.

For your curiosity

📺 Documentaries:

- Black Gold (2006) — Sundance-winning documentary following Ethiopian farmers through the global coffee trade

- The Coffee Trail — Journey through coffee supply chains from farm to cup

📚 Books:

- “The Coffee Paradox” by Benoit Daviron & Stefano Ponte — Academic analysis of global coffee markets and development

- “Globalization and Its Discontents” by Joseph Stiglitz — Nobel laureate’s insider view of international trade

🎧 Podcasts:

- NPR Planet Money — Economics explained through everyday items like coffee

- How Did This Get Here: Coffee — Supply chain deep dive from NPR’s 1A

🌐 Interactive Resources:

- Visual Capitalist: Coffee Economics — Interactive breakdown of the $270B coffee supply chain

- World Economic Forum: Coffee Supply Chain — Comprehensive supply chain visualization

🤝 Organizations:

- Fairtrade International — Working with 838,000+ coffee farmers globally

- Fair Trade USA — $31M in Community Development Funds generated in 2021

Sources

Market Data and Economics

- Coffee Market Analysis - Precedence Research - Global coffee market valued at $245.2 billion (2024)

- ICO Coffee Market Report - International Coffee Organization official statistics

- USDA Coffee World Markets and Trade - Production and trade forecasts

- World Bank Commodity Markets Outlook - Coffee price analysis (58% increase in 2024)

Academic Research

- Coffee Supply Chain Power Analysis - American Journal of Agricultural Economics - Value distribution research showing farmers receive 5-13% of retail prices

- Utrilla-Catalan et al. (2022) - Sustainability - Network analysis of growing inequality in coffee value distribution

- Steven Topik - Coffee Market History - Historical analysis of coffee commodification from 1500-present

Trading and Market Structure

- ICE Coffee C Futures - Arabica coffee pricing benchmark (37,500-lb contracts)

- FRED Economic Data - Federal Reserve coffee economic data series (1973-2025)

- Trading Economics Coffee Prices - Real-time coffee futures (350.41 USD/lb, +42.20% YoY)

Supply Chain and Infrastructure

- World Economic Forum - Coffee Supply Chain - Comprehensive supply chain analysis

- Visual Capitalist - Coffee Economics - Value chain profit distribution visualization

- Oxfam - Cereal Secrets Report - ABCD companies controlling 70-73% of global grain trade

Historical Context

- UNESCO Silk Roads Programme - Historical spice trade routes

- Library of Congress - East Indies Trade Maps - 18th-century coffee trade documentation

- Wikipedia - Spice Trade - Comprehensive historical overview

Fair Trade and Development

- Fairtrade International - Working with 838,000+ coffee farmers through 656+ certified organizations

- Fair Trade USA Coffee - Alternative trading model statistics and farmer impact data

Still curious?

Want more fascinating explanations about the hidden systems shaping our world? Subscribe to the RSS Feed.